ABUNDANCE OF FORMS, IDEAS AND COLOURS OBSERVED IN RETROSPECTIVE

On the Aesthetic Challenges of Reshat Ahmeti’s Exhibition

When the art of Reshat Ahmeti, distinguished by its internal coherence, is observed in retrospective, the first things that come to mind are its completeness and excellence, and the artist’s adoration of permanence.

Through distinctive and masterly contemplation, Reshat declares that nothing is abstract, and that, from a philosophical point of view, art is but a metaphysical act of life. Reshat Ahmeti’s paintings strive to achieve concreteness in a perfect way, both from the aspect of representing it through the figure and from the aspect of their subject matter and ideas that nurture his work. In this context, I would describe Reshat Ahmeti’s paintings as a philosophy of life, applied and made concrete through form and colour.

The leitmotiv throughout most of his work is the geometric figure and the art symbol as the expressive form of artistic stimulation. He builds a passionate artistic individuality which, to paraphrase Albert Camus, I would call the “solitary satisfaction of a creative person.” The notion of solitary creative work is in perfect harmony with the ideational subject matter of human existence and survival in this part of the world in both time and space. I am fascinated by the way in which, in his previous cycles, he adopted a unique ethnological and ethnographic motif, taking care not to surrender to folkloric provocations, but to raise the ethnological signs and motifs to the level of modern art, in constant relationship with existence and the beauty of humankind.

Looking at Reshat’s artistic work in retrospective, we come to understand that it is the result of a long exploration, during which he has created a number of special codes and geometric figures, and several brilliant combinations which he uses to treat the ideas and subjects that concern him using the medium of painting. It is the geometry of figure and the “metaphysics” of colour that represent his two supreme achievements. With their help he goes on to explore successfully the architecture of the free world, so rich in emotions and spirit from the subjective, cultural and historical aspects.

Observing the liveliness and dynamism of Reshat Ahmeti’s paintings, I am amazed how an artist, developing in fairly constrictive social and cultural circumstances, has succeeded in capturing and mastering such essential, existential motifs and subjects. This achievement can be explained by the self-confidence of Camus’s “solitary satisfaction,” which is actually a precondition for any genuine creative work: just as Man does not need to ask for permission to exist, think and express himself, in the field of the arts he should follow his feelings and emotions in the most individual and boldest way possible.

Using exquisitely warm colours in his paintings, Reshat Ahmeti “mitigates” the totalitarian chilliness of Balkan social reality through the ethnographic warmth of a Mediterranean approach, by which, using his paintings, he arouses a profound human nostalgia about things we have worn, things we have used as a cover to protect ourselves from the chill. All of this is presented intellectually and visually through the carpet and the symbol of the red and black binomial, which cannot be deciphered easily, as Reshat holds onto an old principle in art, according to which difficulties during the creation and reception of a work are in direct proportion to artistic satisfaction, meaning that the more we invest in the creation and reception of a work of art, the greater the artistic satisfaction we experience vis-à-vis that work. I would like to single out this characteristic of Reshat’s paintings, in which the social and cultural indigenousness of a way of life, the motifs of textile decorations, are raised to the level of artistic modernity in an exquisite creative manner. His creative advantage is the fact that he does not imitate, but includes the idea within a semiotic context, making his painting an open work that can be explored and approached from a variety of aspects, of which I would single out two: (1) The painter’s object (the canvas) as an organized artistic object, i.e. as an artistic being with a coherent structure and rich layers, and (2) Symbolism (the fluid part), communicating openly with a multitude of ideas, messages, dynamic associations, that act as a kind of journey through the painter’s narrative woods, definitely impenetrable from the interpretative aspect.

As far as the first component is concerned, the means of symbolism and structuralism, the various textures are united, and the factor that unites them all is colour, which itself sometimes becomes a form. This fact shows that the painter has an excellent command of colour, alongside with his mastership of the symbol as a unique means of expression. These elements form what I would call the integrity of an artist: it seems to be nourished by a “floodlight” placed in a particular spot; the shadows created in this way then generate the visual quality, safety, clarity, and also the fluid forms, mists that seem to come and go in the background, expressing a dilemma, an ambivalence, which only make his painting richer, transforming it into an open work receptive for a multitude of interpretations.

On the other hand, however, Ahmeti’s paintings confirm the fact that he has interiorized and mastered lyrical geometricization as a leitmotiv of his paintings. There, art continues to act as both a discovery and exploration; there, the concrete form, the real world, is revealed, represented and interpreted in different ways, in both time and subject matter.

This inclination towards exploration is apparent in his last cycle, in which he uses physical appearance together with the area encompassed by the blind frame and canvas, giving a real three-dimensional quality to the painting.

In his most recent cycle, which is both built upon his previous work and a novelty at the same time, Reshat Ahmeti plunges into the ontology of the canvas, cutting geometric forms such as the square, triangle or circle. He does not limit himself to colour as the only means of artistic expression, as he has done so far, but he does also confer this function on the canvas, with the help of which he achieves genuine three-dimensionality. This artistic striving brings us back to the original conclusion that the artist Reshat Ahmeti demands a lot from his painting. Apart from ideas and abstraction, he is also interested in the concrete: he is not satisfied with achieving an illusion or functionality; he tends to get to the tangible – the human freedom of action – since, to quote Nietzsche, “only this area of human life can represent life itself in a more transparent manner.”

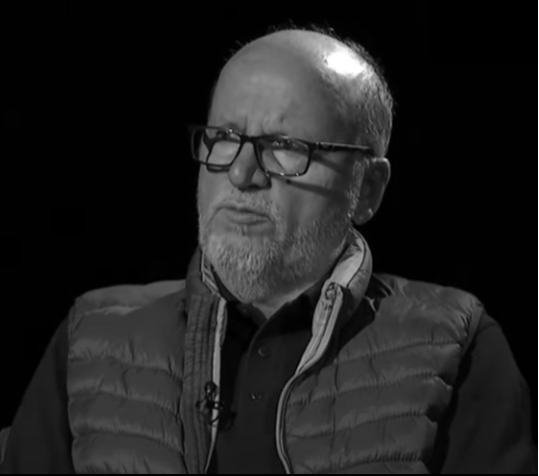

Kadri Metaj, philosopher and aesthetician